In the Bill Clinton-endorsed book The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart, Bill Bishop warns that while America is diverse, “the places where we live are becoming increasingly crowded with people who live, think, and vote as we do,” and that “our country has become so polarized, so ideologically inbred, that people don’t know and can’t understand those who live just a few miles away.” [1] Similarly, Gerald Frug, in Citymaking: Building Communities without Building Walls, writes that “the overall impact of American urban policy in the twentieth century has been to disperse and divide the people who live in America’s metropolitan areas, and, as a result, to reduce the number of places where people encounter men and women different from themselves.” [2]

Indeed it’s hard to tell a story about American urbanization without talking about homogeneity and exclusion. One reason for this is that at least until 1968, “reducing the number of places where people encounter men and women different from themselves” was done explicitly, and with the full cooperation of every level of government, as well as the real estate industry.

While most of the tools used to explicitly segregate people by race and religion have been outlawed, a newer set of subtler methods to produce homogeneous communities implicitly has been developed over the past 40 years This paper will focus on some of the new tactics of exclusion used by developers of private master-planned communities. [3]

The arsenal of exclusion

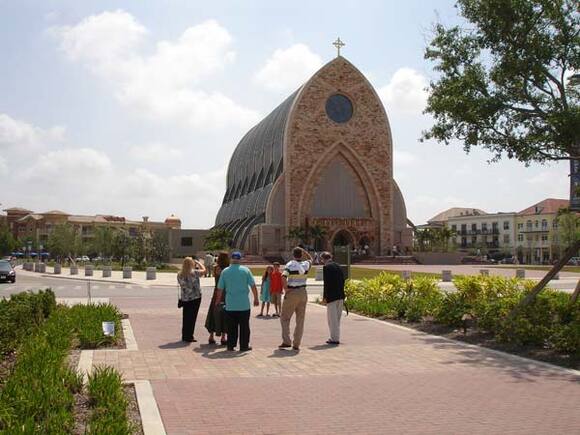

Ave Maria is a private master-planned community near Naples, Florida (fig.1). While ostensibly marketed to “every dream, every lifestyle and every family,” [4] it is in fact the vision of Ave Maria to create, as the community’s founder put it, “a truly Catholic community.” [5] Ave Maria features a Catholic university (“the first new University founded with Catholic principles in the United States in the last 50 years!” [6]), a huge churchlike “Oratory” (fig. 2), and street names such as “Pope John Paul II Boulevard,” “Avila Avenue,” and “Assisi Drive” [7] (fig.3). At the insistence of Ave Maria’s founder, the archconservative businessman Tom Monaghan, the community’s retailers are prohibited from selling contraceptives and pornography.

Themed and gated private master-planned communities such as Ave Maria have been a staple of 20th century urbanization in the United States and the creation of homogeneous communities has been the implicit goal of many of these communities. Over the decades, the developers and designers of master-planned communities have assembled a full arsenal of tools to foster homogeneity by controlling access to planned communities.

While what is arguably the first master planned community in the United States—Llewellyn Park—restricted access with a gate, access to early planned communities was primarily controlled through racial deed restrictions and restrictive covenants. Even before the first zoning codes were put in place in the 1910s and 1920s, racial deed restrictions and restrictive covenants on private developments spelled out in detail which uses were and weren’t allowable. Expressions of “fears of almost everyone and everything,” [8] these covenants not only excluded African- and Asian-Americans, Jews, the working class, and in many cases the middle class: they also prohibited a range of behavior deemed detrimental to the preservation of property values. At least until the Great Depression, when developers tended to be less picky about who to sell their homes to, the use of racial deed restrictions and restrictive covenants became commonplace, and could be found in almost every American city. To make matters worse, when the Federal Housing Administration (the New Deal agency established to guarantee long-term, low interest mortgages), assessed the credit risk of America’s communities, they looked highly on the use of racial covenants, and typically gave “protected” communities a higher rating, creating a second-wave of the covenants. As David Freund points out, the FHA’s own appraisal manual, working from widely held assumptions that racial integration would undermine white neighborhoods and that properties in non-white or “mixed” neighborhoods were risky investments, required the “[p]rohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended.” [9]

Gates, racial deed restrictions and restrictive covenants weren’t the only means by which developers of master planned communities restricted access. By stipulating minimum lot sizes and minimum house prices, and by building communities consisting only of single-family houses, developers were able to restrict access to those who didn’t have the means to buy expensive single-family homes on large lots. And it should be pointed out that developers of planned communities benefitted from the exclusionary tactics of others. Prejudiced developers, for example, could count on local real estate brokers—who in most cities took a sworn oath to never introduce “inharmonious elements” into white neighborhoods—to “steer” these elements away from their developments. If these brokers didn’t practice steering, they could count on local neighborhood associations to boycott them. Big city churches regularly used the pulpit to warn parishioners about the evils of integration, big city newspapers editorialized in favor of segregation, and homeowners themselves deployed or threatened violence to send a clear signal to blacks brave enough to cross the color or religion barrier. Starting in the 1960s, suburban municipalities learned to use “expulsive zoning,” a strategy that entailed rezoning African American neighborhoods for business, or for low density, thereby preventing neighborhood expansion. In short, prejudiced developers of master planned communities weren’t exactly fighting an uphill battle.

Racially restrictive and religious covenants were declared unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948, and then entirely prohibited by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, [10] which outlawed discrimination in the sale, rental, and marketing of homes, in mortgage lending, and in zoning. But as we were painfully reminded by the 2010 census, most Americans still live in environments that are radically segregated, especially by race. How can we explain this? Is segregation merely the legacy of tools—like Racial Zoning or Racial and Religious Covenants—that no longer operate? Or are there newer, subtler tools that continue to produce homogeneous communities such as Ave Maria? This essay supports the latter claim. We will look at three such new tools as they apply to private master-planned communities: Conditions, Covenants, and Restrictions (CC&Rs), Exclusionary Amenities, and lifestyle marketing.

The arsenal of exclusion continued

CC&Rs are the planning codes that govern private communities. A developer typically drafts the CC&Rs along with the plan for a new community. Once built, the community is turned into a Common Interest Development (CID) with a mandatory Homeowner Association. The Board of the Homeowner Association (the de facto private government of the community) is then responsible for the management and maintenance of the community as well as the enforcement of CC&Rs. These codes regulate and restrict allowable uses (Ave Maria’s CC&Rs for example prohibit abortion clinics, abortion counseling, facilities “performing embryonic stem cell research or other activity involving the destruction of human embryos or any facility performing in vitro fertilization or human cloning” [11] among other things), exterior design (from landscaping to holiday decorations and the types of cars allowed in driveways), age and behavior (ownership of dogs, level of noise, visits by grandchildren, etc). [12]

Aside from CC&Rs, a second, subtler (albeit no less powerful) tool of restricting access to private master planned communities is what the legal scholar Jacob Strahilevitz has termed the “exclusionary amenity.” [13]

A typical feature of Common Interest Developments are shared amenities: While the homes in these developments are individually owned, the golf courses, tennis courts or swimming pools are held in communal ownership by all residents. Homeowners pay for the maintenance and management of the amenities through monthly fees to the Homeowner Association. It is through these fees that shared amenities turn into exclusionary amenities: Someone who is not interested in playing golf is presumably not interested in paying for the management and maintenance of a golf course and is therefore not going to move into a community that levies fees for such an amenity. Given the fact that in the 1980s and 1990s only about three percent of American golfers were African American, the golf course became an effective proxy for all-white communities. As Strahilevitz writes: “An exclusionary amenity is a collective good that is paid for by all members of a community because willingness to pay for that good is an effective proxy for other desired membership characteristics,” such as race or religion.

Ave Maria features an exclusionary amenity par excellence: the huge church-like “Oratory” at the center of the community is a shared amenity, paid for by homeowner’s fees. While it is de jure illegal to exclude non-Catholics from settling in Ave Maria, the Oratory de facto makes it very undesirable for anyone who doesn’t want to pay monthly fees for the management and maintenance of a giant Catholic church. The Church as Exclusionary Amenity is a tool to create a homogenous, “truly Catholic community.”

Ironically, the precedent for Common Interest Developments such as Ave Maria can be found in the progressive American garden city of Radburn, New Jersey (fig.4). Planned in the late 1920s by Clarence Stein and Henry Wright (the founders of the Regional Plan Association of America), Radburn was based on Ebenezer Howard’s ideas of communal ownership and became the model for CIDs: the planning and construction of Radburn’s shared amenities and individual homes was handled by the (non-profit) City Housing Corporation with the backing of real estate developer Alexander Bing. With the sale of houses and plots, the shared amenities were passed on to the Radburn Association, which in turn charged homeowners fees for the management and maintenance of communal spaces.

Of course Radburn’s communal amenities weren’t churches or golf courses, but large green spaces in the middle of housing clusters, reminiscent of the village greens in the New England small towns that served as the prototype for RPAA’s Gemeinschaft ideal (fig.5).

After the second World War, Radburn’s model of communal ownership and governance was increasingly adopted by private developers, encouraging the Federal Housing Authority to begin providing mortgage insurance for planned communities in the 1960s. Municipalities increasingly accommodated planned communities through more flexible zoning models such as Planned Unit Development zones (PUDs). In its traditional form, zoning regulates size, use and density of parcels on a lot-by-lot basis. In a PUD, density is aggregated and applies not to individual building lots within a development but to the entire parcel. This creates the potential for areas of clustered buildings at higher densities as well as larger open spaces to preserve natural features or build golf courses (fig.6).

PUD also allows for a mix of housing types and land uses, making possible the proliferation of denser, neo-traditional communities during the real-estate boom of the late 1980s. The combination of neo-traditional design, highly restrictive CC&Rs, relatively high residential densities, some non-residential functions and communal amenities such as “nature reserves,” golf and polo courses in New Urbanist communities such as Seaside, Florida and Kentlands, Maryland became the formula for the majority of new planned communities during this time. [14]

Since the early 1990s then, the spectrum of planned communities has diversified in astonishing ways. Today, there are not only neo-traditional golf course communities and private master-planned communities for Roman Catholics, but also communities targeted to Muslims, gay retirees, organic farmers, hobby astronomers, civil war re-enactors, wine-makers, and aviation enthusiasts. [15] Each of these communities comes with its own CC&Rs and exclusionary amenities. Serenbe, a 900 acre site southwest of Atlanta, transforms one of the last undeveloped areas in the metropolitan region into what is marketed as an ecologically sustainable, walkable, and culturally diverse neighborhood. Included in the community is a 25-acre organic farm that provides heirloom tomatoes at Serenbe’s weekly farmer’s market (fig. 7). (Serenbe is described as a “visual blend of New England mill town and Southern farming backwater, with a bit of industrial modernism thrown in.”) Jumbolair, a 380 acre “fly in community” was built complete with private runways (fig.9).

It’s important to note that not until fairly recently did developers feel a need to embed things like golf courses, churches, organic farms, vineyards, and runways into their master planned communities. If the CID model and PUD zoning was one factor that led to diversity in product types, another was market fragmentation. In the post-war building boom of the 1940s and 1950s, master planning a community was in many ways simpler: millions of returning GIs needed a house—any house—and a glut of large, mass-produced, homogeneous subdivisions like Levittown, NY were built to supply the demand. So long as these communities were sufficiently “protected” against “inharmonious elements,” they were likely to find an audience. More recently, however, developers have felt a need to distinguish their master planned communities from those of their competitors. For developers of master planned communities today, it’s not enough to build a plain subdivision: to sell homes, developers often try to manufacture a “lifestyle,” which, judging from the glossy brochures that developers use to advertise their communities, has become an amenity people crave, just like granite countertops, hardwood floors, and three-car garages.

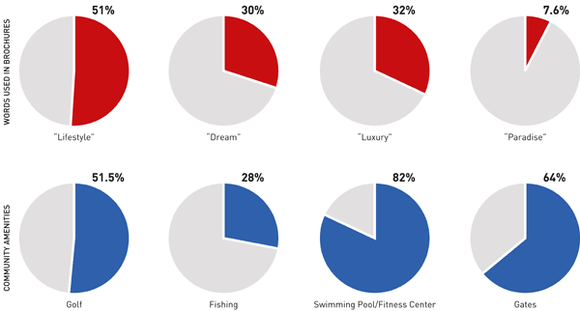

Indeed, the extent to which this word “lifestyle” pops up in real estate brochures is remarkable. In a sampling of 316 brochures of private, master planned communities collected and examined for the purposes of this essay, the word “lifestyle” was used 269 times, and was used in over half the brochures (fig.11).

Through soft-focus, often immaculately-staged pictures of people enjoying this or that community’s various amenities, and though elaborate texts that deploy carefully-selected historical references, these brochures are meant to assure would-be home-buyers that if they moved to, say Ruskin Heights in Fayetteville, AR, they would be living among people just like themselves (in this case, others who might like a John Ruskin-inspired “arts and crafts community”). By including images primarily of children playing unsupervised in pristine natural settings, the brochure for Eagle Springs in suburban Houston suggests that it is first and foremost a safe, non-urban place to raise children. The brochure for Washington’s Issaquah Highlands sends a signal to environmentally-conscious home buyers by editorializing that “Living Green (TM) is all about making choices that help us all tread more lightly on the earth,” and by foregrounding its energy star-certified homes.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, most of the brochures appeal to Americans’ seemingly limitless appetite for safety, status, nostalgia, and leisure. 64% of the brochures sampled bragged about being gated, 32% used the word “luxury,” and 30% contained the word “dream” in describing their community. 82% advertised a swimming pool, 51.5% of the brochures advertised a golf course, and astonishingly, 28% advertised fishing as an amenity.

Most of the references to luxury are rather generic (e.g., “welcome to the good life”), but some attempt to connote very specific associations. Portsmouth, RI’s Carnegie Abbey, which advertises “old-world elegance and the timeless nobility of riding,” has homes named “The Royal Turnberry,” “The Royal Dornoch,” and “The Puritan.” Carnegie Abbey’s brochure has a picture of JFK and Jackie O on its cover, and makes constant references to Newport as playground for the American elite. Cottesmore Village, an “equestrian community” just outside Camden, South Carolina, includes expansive facilities for polo, fox-hunting, dressage, and trail-riding.

Appeals to what Leo Marx called “sentimental pastoralism,” and the desire among so many Americans for a non-urban lifestyle abound in the brochures. North Carolina’s Falls Cove, for example, is the “place where Peace met Quiet.” In Youngsville, NC’s Hidden Lake, you can “escape the commotion of the city by coming home to the tranquil surrounding of a breathtaking lake.” The brochure for Wolf Creek Ranch in Park City, Utah boasts that Wolf Creek is “where Father Time can’t change Mother Nature.”

General nostalgia for a time when things were better figures prominently into the brochures as well. The brochure for Georgia’s Savannah Quarters explains that in Savannah Quarters, “an unmistakable old-world charm greets its visitors and residents.” The Peninsula Neighborhood in Iowa City, IA states that “they don’t build ‘em like they used to. But we do.” The following quote from the brochure for Richmond Hill, GA’s Ford Plantation—which sounds like it was taken from Lewis Mumford’s 1939 Garden City propaganda film The City—sums up the general nostalgia found in so many of the brochures: “Someday soon, you will bring your family home to The Ford Plantation. They’ll take to the place as naturally as the heron and ibis take to our marshland. While your kids and ours run barefoot on the lawn, we’ll share a pitcher of something cold and a basket of corn bread.”

More concrete historical references in the brochures are perhaps more troubling. Many communities merely want to appear old and dignified (the brochure for a newly-completed community called Palmetto Bluff features a timeline spanning from 1524 to the present), but many southern communities take pains to connect themselves to antebellum traditions. The brochure for Fayetteville, PA’s Penn National Resort begins by wondering: “If only Robert E. Lee knew what was to transpire around him when he stayed in the White Rock Manor House nearly 140 years before.” The brochure for Iuka, MS’ Pickwick Pines notes that “The [nearby] battle of Shiloh, Tennessee reflected all the conflict and valor that have come to represent the Civil War,” something that is “worth remembering.” The brochure for South Carolina’s Mount Vintage boasts that the property was “elevated to one of the grandest plantations of the area in the early 1800’s, is now the site of our thriving community,” adding that “our focus is to preserve the history and beauty of the Plantation.”

As suggested by the high percentage of golf courses and swimming pools found in the communities we sampled, leisure features prominently in the brochures. North Carolina’s Champion Hills advertises itself as “an endless vacation.” Alabama’s The Waters boats “it’s not a vacation home, it just feels like one.” In Florida’s Palencia, “your new lifestyle of year-round resort living begins at the gated entrance to Riviera and never ends.”

Brochures often choose to emphasize a community’s architecture as a means of communicating a given community’s lifestyle. The brochure for Dallas’s Urban Reserve highlights its pseudo-Modernist, “high design” houses, whose names include Cube House, X-Acto House, Color Clock House, and See-Through House. (All of these are situated on “Vanguard Way,” the development’s main street.) The brochure for Fall’s Cove, NC highlights the community’s “unique twist on the traditional Craftsman style home.” New Mexico’s Nature Point makes a point of emphasizing its “over-sized, hand peeled vigas and massive rough-sawn beams from the nearby Jemex Mountains, you will be awestruck by the beauty of such massive timbers, authentic latillas and corbels will also complement the southwest imagery.”

Glossy real estate brochures, however, are just one tool of lifestyle marketing. Another is steering. Especially before the Fair Housing Act made the practice illegal in 1968, real estate steering was a tried and true method that was employed to keep communities homogeneous. Racial steering—one famous kind of steering—refers to the practice whereby real estate brokers guide prospective homebuyers towards or away from certain neighborhoods based on their race. Racial steering might mean advising prospective homebuyers to purchase homes in particular neighborhoods on the basis of race, or failing that, on the basis of race, to show, or to inform buyers of homes that meet their specifications.

Private Mountain Communities is an Asheville, NC based company that describes itself as a "trusted authority on Western North Carolina living." A broker of sorts, Private Mountain Communities "matches families with communities that complement their personal taste and lifestyle." Two things stand out about this company. One, they have a storefront—or what they call a "state of the art Discovery Showroom"—in downtown Asheville where would-be home-buyers can consult with "independent community advisors," preview community brochures, DVD’s and "use interactive explorations tools" to find the community that is right for them. Second, on their website, there is something called a "Community Finder:" an application that "guides you through an easy questionnaire that analyzes your unique interests and lifestyle preferences, such as architectural tastes and preferred amenities, to produce a short list of communities that are right for you." A video on the website underlines the questionnaire’s science, stating that the questionnaire is "an algorithm that really takes you down the right path so that you are getting into a subset where you fit. A concept that represents all the communities in this area in an unbiased way.”

The questionnaire is actually more benign than it sounds, asking questions like: "Which of the following area activities are essential to your decision to purchase property?" and "Which of the following on-site amenities are essential to your decision to purchase property?" But Bill Bishop describes something much less benign in The Big Sort. Bishop writes about a questionnaire that is given to prospective homebuyers in an Orange County, CA development called "Ladera Ranch" whose questions try to get at the homebuyers’ values (for example Do you “like to experience exotic people and places?” Or, do you believe “extremists and radicals should be banned from running for public office?”). Here is Bishop: "The Ladera Ranch developers built one section of their subdivision for those who see the Earth as a “living system.” (It’s called “Terramor” and features bamboo floors, photovoltaic cells and, according to the developer, houses that ’might have a courtyard that conceals the front door...kind of cozy and nest-like.’) Across the way is a community for those the developer labeled ’Winners.’ In Covenant Hills, houses are more colonial than craftsman."

What is happening here if not steering?

Brochures, Walk-in Storefronts and Questionnaires—like CC&Rs, exclusionary amenities, are a part of a new technology of exclusion, an answer to the question: how do you create homogeneous communities when you have Fair Housing legislation that prohibits you from using all the other methods that succeeded so well previously? The crucial thing here is to shift race and class to things that become a proxy for race and class—usually, something vague and seemingly benign called a “lifestyle”. The purpose of these “soft” tools of exclusion is the same: they exclude “undesirables” by inconveniencing them or by making them feel unwelcome.

[1] Bill Bishop, The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008.

[2] Gerald E Frug, City Making: Building Communities Without Building Walls, Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1999.

[3] Robert Charles Lesser & Co. defines master-planned communities as “large-scale developments featuring a range of housing prices and styles, an array of amenities, and multiple non-residential land uses (such as commercial, hotels, and educational facilities).” Our definition is analogous. See http://www.rclco.com/pdf/Feb222008510_MPC_Press_Release_2-22-08.pdf.

[4] Ave Maria’s Marketing Brochure.

[5] Tom Monaghan, quoted in The Angelus (Ave Maria University’s newsletter), January 2005.

[6] Ave Maria University’s website.

[7] Refering to St. Theresa d’Avila, the 15th century mystic that fueled much of Counter Reformation dogma and St. Francis of Assisi, founder of Franciscan order.

[8] Robert M Fogelson, Bourgeois Nightmares: Suburbia, 1870-1930, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

[9] Indeed as Antero Pietila notes in Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, this worked both ways. Pietila notes that the developer of an early black suburb near Morgan State University in Baltimore called Morgan Park used racial covenants to forbid whites from living there - a tactic that earned the neighborhood what was perhaps the only “B” rating ever given to a black neighborhood by a Federal appraiser.

[10] In the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer decision.

[11] “Amended and Restated Declaration of Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions of Ave Maria Town Center I / Core,” November 2007.

[12] CC&Rs are enforceable on a state level, as there have been many court cases that challenged them and failed. Evan McKenzie writes about a number of such cases, such as the case in Boca Raton, Florida, where a homeowners association brought a homeowner to court because her dog weighed more than the allowable 30 pounds. See: Evan McKenzie, Privatopia: Homeowner Associations and the Rise of Residential Private Government, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

[13] Jacob Strahilevitz, Exclusionary Amenity,” in: Tobias Armborst, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore, The Arsenal of Inclusion and Exclusion, Barcelona: Actar, 2011.

[14] See Paul L Knox, Metroburbia, USA, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008.

[15] To really get a flavor of the spectrum of interest-based communities, browse the Intentional Communities Directory , where you will find the following: A few men with a large tract of land in the northern foothills of the Missouri Ozarks are looking for like-minded, agriculturally-inclined, eco-friendly artisans free from the bonds of organized religions and political correctness to join them in establishing a community in celebration of “all aspects of living from the times of our ancestors before the various diasporas into others lands and modern cultures.” A woman with some acreage outside Indianapolis wonders whether there might be others interested in starting a community “devoted to astral travel and telepathy, and possibly telekinesis.” An itinerant group of a dozen or so followers of “the way of the heart” are advertising availability in a bucolic new residential community called “Adidam.” The catch? To live there, “one must be a formally acknowledged devotee of Adi Da Samraj.” An advertisement for the “Alone Together Hermitage” invites people to join a community “of hermits and loners living together for the mutual benefit and protection of the whole,” where “great efforts are taken by all to ensure that the sanctity of that solitude is never broken under any circumstances,” and “a sophisticated process of communication and notification has been developed so that no member is required to interact with any other.” And in another neck of the woods, a self-identified loner is looking to connect with “free-thinkers and underground intellectuals . . . afraid to commit to communities” in order to “pool resources and start an outsider’s community . . . for those familiar with rejection.”