- The Kenyan Greenport

In the world of international development cooperation an interesting dynamic is taking place: globalization. Neo-liberal ideologies give space for an expanded connectivity between policy making arenas and modes of policy development. The reduction of political boundaries is most evident within Dutch development cooperation. In recent years classic bi- and multilateral development aid was modernized by the introduction of extensive private sector subsidies, giving rise to new complex public-private partnerships. Within this ‘Aid to Trade’ discourse targeting market dynamics is argued to lead to more meaningful development than voluntary transfers of resources. Many have contested the shift from aid to trade, even though its intricate workings are not yet fully understood. In this short-read I present my experiences unpacking the ‘black box of development’ of the ‘Regional Agricultural and Industrial Network’ (RAIN) project in Nairobi, Kenya.

In 2015 DASUDA (Dutch Alliance Sustainable Urban Development Africa) partnered with RVO (the Netherlands Enterprise Agency) to initiate RAIN and received governmental funding to do so. RAIN is based upon the well-established Dutch Greenport concept: large and well-connected food production, processing and transportation hubs located in peri-urban areas (figure 1). In such hubs proximity is key to success since it creates numerous social, economical and environmental advantages compared to classic dispersed systems. From a more political perspective, the character of RAIN is two-faced: one aim is to stimulate structural cooperation between Dutch and Kenyan governments in perusing food security and the other aim is to propagate Dutch agri-business interests along the way. This notion of ‘win-win’ fits the bigger Aid-to-Trade concept seamlessly. The Dutch embassy in Kenya has food security at the top of its agenda and Dutch market actors have a strong competitive position in the agribusiness sector. It was for this reason that RAIN was admitted: it has great potential to create meaningful development whilst simultaneously opening-up new Dutch market opportunities.

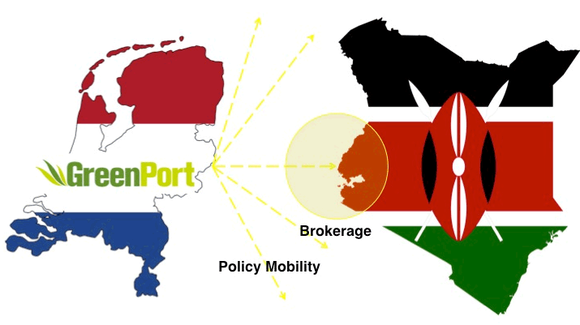

Moving away from the vertical techno-political context we now focus on the more horizontal socio-geographical processes driving the development of RAIN. Policies, concepts and ideas cannot simply be traced from sites of origin to sites of implementation. In order to understand its trajectory we need to focus on the concepts of mobility and brokerage (figure 2). As already mentioned policies have become commodities on global markets. It is when a policy is actively transferred from originator to recipient that the fascinating concept of brokerage occurs. Brokerage entails the interactive processes of negotiation between key stakeholders aiming to tailor-fir foreign concepts to local conditions. Within this process ‘brokers’ play essential roles. They initiate the policy transfer process and manage the negotiations. Brokers seek to reach a mutual understanding of urgency by interlocking interests, but how do you reach consensus in a multi-stakeholder party with different and often contradicting institutional arrangements? For such activities no normative systems are in place, it’s an elaborate and delicate process of interaction ridden with uncertainty.

Brokering RAIN was a resource and time demanding process. Many unforeseen events and hurdles needed to be dealt with, many more then originally accounted for. A mismatch between project planning and actual implementation occurred challenging the development process and almost brought it to a complete halt. However two resourceful brokers, one from the RVO, Caroline Warmerdam, and the other from DASUDA, Remco Rolvink, overcame these problems. Acting as intermediaries between the very different worlds of Kenya and the Netherlands they have proven critical in the success of the project-planning phase. Next, three of the most critical hurdles to RAIN development, and how they were overcome, are discussed.

Shared understanding

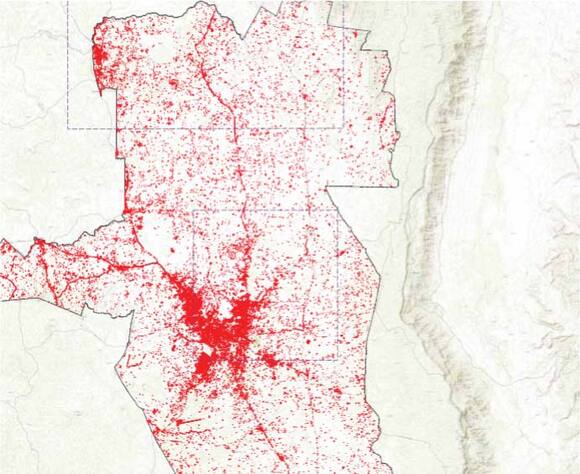

Spatial developments require vast amounts of space. Before selecting a location political planning tools like zoning need to be in place to ensure sufficient available space from urban sprawl. However, local governments lacked a sense of urgency to the matter. In order to reach a shared understanding of its urgency brokers used GIS and Remote Sensing technologies to construct a strong visual representation of ‘Real Urbanization’ (figure 3). The map was received with astonishment and awe, resulting in a strong commitment to develop relevant planning tools not just for RAIN but for a stronger planning in general.

Commitment, accountability and ownership

The overal neglect of procedural commitment by local actors appeared a serious threat. Even after setting up strong rules of engagement, collectively set agendas, preparations and deadlines were ignored and timely attendances to meetings were exceptional. After reducing efforts for slacking actors together with increasing efforts for eager ones a competitive environment was created and accountability was enforced. Also, while the project matured its exposure increased, tapping into the pride of its stakeholders. These mechanisms fueled a will to be part of the project, a sense of ownership, and the commitment to actively engage and respect collective rules.

Participation, engagement and data-interpretation

Local stakeholders lacked general planning expertise, disbalancing power-relations. In order to reach a more equal environment stakeholders needed to be engaged in planning related activities: ‘learning-by-doing’. Several interactive methods like brainstorming, roleplaying and collective mapping were applied (figure 4). Working together in fun and safe game-settings increased stakeholder participation engagement. Also, the importance of data collection and coordination became apparent. This led to an extension of the project, incorporating GIS workshops and follow-ups. Local stakeholders overcoming these issues by learning new skills is of mayor importance to reach trust and independence.

This short-read presents the intricate workings of Dutch privatized development cooperation by using RAIN as a case and brokerage as a lens. It shows how powerful and important actors can be in brokering development and how fluid, headstrong and open-minded they need to be to deliver. With this fundamental understanding first steps are made towards a more comprehensive understanding of privatized development cooperation. However, more comparable in-depth researches need to be conducted in order to normalize brokerage methodologies and improve its workings.